This Is Why I’m Not A Hotel Receptionist

1982

It was the last day of a family summer holiday in France, I was 14 years old. My dad finally let me do the thing I had been itching to have a go at all fortnight. He actually let me hold his new Pentax ME Super camera and take one picture with it. One single picture, film was expensive and not something to be trifled with or wasted. Make sure you look before you leap.

I loved it. I loved the buttons and dials and metallic feeling of it, the strange symbols, the odd, illogical numbers and markings, the way I could frame the world to my liking through the viewfinder and bring things in and out of focus. I was a shy kid, confident in my thoughts but nervous physically. I didn’t like the way I looked. I thought my sleepy eyes made me look dozy. Even now people think I look tired even when I’m wired to the sky. Having the camera up to my face allowed me to both hide from the world and confront it at the same time. The camera had a gold sticker on it with the logo of the Asahi Optical Company of Japan that said “PASSED” in block capital letters, as if to say that this item was of such complicated and vital construction it required extra approval to leave the factory from those whose name it bore. It was relevant.

All these years later I have no recollection of what I photographed that summer’s day in Brittany in 1982. I only remember that I was dying to do it again. Bit by bit my dad began to trust me with the camera and I was allowed to use it more often. Eventually, he seemed to stop using it altogether and it became mine by osmosis. At that point it was a hobby and nothing more.

Sometime later, months or years, the memory and recollection of time and place is compressed by the passing of time itself, I was in the school library and came across a book, ‘Black & White Memories’, by a photographer called David Bailey. I cannot tell you enough what an evangelical, Saul on the road to Damascus moment this was. The pictures in that book were the key to a door that opened into a room that I didn’t even know existed. A room that was both unmistakably familiar and wholly new. I had fallen down Alice’s rabbit hole into a fantasyland that was more real than the future that had been ascribed to me up to that point, which was probably school, university and some sort of white collar, possibly professional career of security and mundanity. I know I wanted the security because I still crave it now, but I couldn’t face the mundanity. That day in the library flipped my future upside down by confiscating the security altogether and replacing it with the kind of possibility that would entail having to keep my eyes on the road for all time. For someone who looked so sleepy, there was to be no sleeping through life for me. The room that the Bailey book unlocked was a place where photography didn’t have to be weddings and repetitive family portraits. Oh! You can do that. You can do that. You can do this. You can go there. You can meet these people. You can meet those people, who, incidentally, are quite different to these people.

The way he cut off the top of peoples’ heads and went straight to the eyes. He had a style of photographing pairs of people and getting their heads to tilt in opposite directions to each other, which created a symmetry that was almost hypnotic. All that starkness. As Ian Dury once sang about Gene Vincent:

White face, black shirt

White socks, black shoes

Black hair, white strat

Bled white, died black

All extraneous details eliminated. No ambiguity. No frills, no fuss, no flim, no flam.

All the time it’s important to remember that this took place before the internet existed. Finding stuff out involved physical effort. You couldn’t just sit in your bedroom on your arse. No, you had to go to places: libraries, bookshops, museums, art galleries, the cinema, record shops. You had to want to find it badly enough to actually get dressed. Starting with Bailey I learned about lineage, about Penn, Avedon, John French, Cartier Bresson. From there to others. Ralph Gibson, Bruce Weber, Helmut Newton, Jacques Lartigue, August Sander, Paul Strand, Joel Meyerowitz, William Klein, Arnold Newman, Elliot Erwitt, Lee Friedlander, each one opening another door to their influences and persuasions.

When you’re a boy in your mid-teens in the home counties of England in the early to mid eighties, things like this are the punch in the face you need if you don’t want your life to be something that begins at 5.30pm on a Friday every week.

In time, although my interests and tastes in photography have travelled across a lot of ocean, Bailey’s work and story have remained as the Greenwich meridian of my photographic core and even now, when I look at his work all these years after first finding it, I feel that I am back in my home port.

2011

The last time I got a pay cheque that didn’t come from photography was in 1992. I’m in my 20th year as a photographer. I’m as excited by taking pictures now as I was in 1982. The worry of earning a living never subsides though, it’s a burden and it’s the catalyst that keeps these somnambulant eyes open. It’s my daily sharpener. It’s about getting the call. I love the buzz of the call. The gig, the job. I’m not an artist and I have no wish to be an artist. I’m a curious person who feeds his curiosity by taking pictures. After doing this for 20 years I know that there’s no type or class of person that I couldn’t hold a relevant conversation with if I needed to. Sometimes I have to sit at tables next to people whose eyes glaze over when they realize I can’t do anything for them, that I have no relevance to their idea of personal advancement. I have a certain level of self awareness. I try not to be boring. My granddad had a great way of putting this. “Try not to be the kind of man that lights up a room by leaving it”, was what he said.

A call comes. From Lucy Davies. She runs Telephoto, the Daily Telegraph’s online photography blog. I love Lucy. She loves photography and, incredibly, she also seems to like photographers. She knows what she’s talking about. Her knowledge has depth and breadth. A conversation with her will always involve me learning something. She reminds me of a much younger version of Elisabeth Biondi, who recently retired from The New Yorker and from whom I have been lucky enough to have been thrown some very juicy scraps now and then, including the one that allowed this story to happen. Lucy has a proposition. Would I be interested in taking part in a one to one conversation with another photographer for the Telegraph that will be recorded and published as a transcription? She wants it to be me with an older photographer and she wants us to talk about the nature of magazine photography and the way it has changed over the last 50 years. Of course, I say. Who will I do it with?

She says, “I was thinking it would be good to do it with Bailey. What do you think?”

A little piece of me stumbles inside. I retain composure, attempt slight ambivalence and proceed thus:

“Yes, in principle, but I don’t know him, I’ve never met him and he will have no idea who I am. If you can persuade him then I’d be glad to do it.”

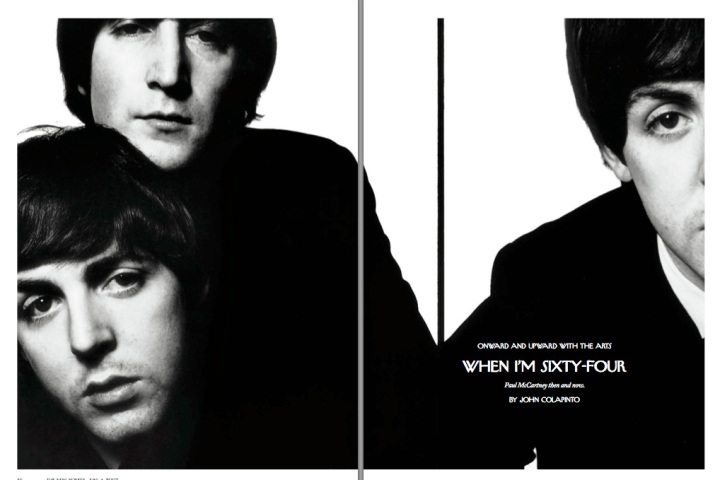

In my head I can see the 14 year old me in the school library again and I have a thought. In 2007 The New Yorker ran a profile of Paul McCartney entitled “When I’m Sixty Four; Paul McCartney, then and now.” The opening spread and the “then” part of that headline was Bailey’s iconic 1965 portrait of him and John Lennon. On the turn page, as the “now” picture they ran my portrait of him, taken in the early years of the 21st century.

I call Lucy back and suggest that this use of mine and Bailey’s work in the same magazine story could be the perfect hook for us to get together. We could begin by talking about photographing the same subject 40 years apart and go from there.

Two weeks later, an email:

From: Lucy Davies

Date: 16 February 2011 18:18:45 GMT

To: Chris Floyd

Subject: Fwd: McCartney – New Yorker

See below. Can you email Danielle and arrange a time to meet? Fngers crossed we are almost there. You will have to charm your way to the last post CF.

xx

———- Forwarded message ———-

From: Danielle Edwards

Date: 16 February 2011 18:15

Subject: Re: McCartney – New Yorker PDF

To: Lucy Davies

Hi Lucy

I think Bailey wants to meet him first to have a quick chat before he commits.

Can we organise a quick chat at Baileys studio? Let me know if you want to schedule with you or direct with him.

Thanks

Danielle

Studio Manager / Personal Assistant to David Bailey

‑_____________________________________________

Tuesday 1st March is the date we agree to meet. It’s a ‘quick chat’. Meet and say hello. It’s St. David’s Day but I’m certain that the David I’m going to meet is no saint. Somewhere on the walk from Euston to his studio off the Gray’s Inn Road I step over a crushed daffodil on the pavement.

Of all the people I know in this business, every one of them seems to have worked or spent time with him. They all have their stories and most of these involve extreme language or confrontations of one sort or another. I’m the only person I know that has never met him or worked with him or have any tales to tell.

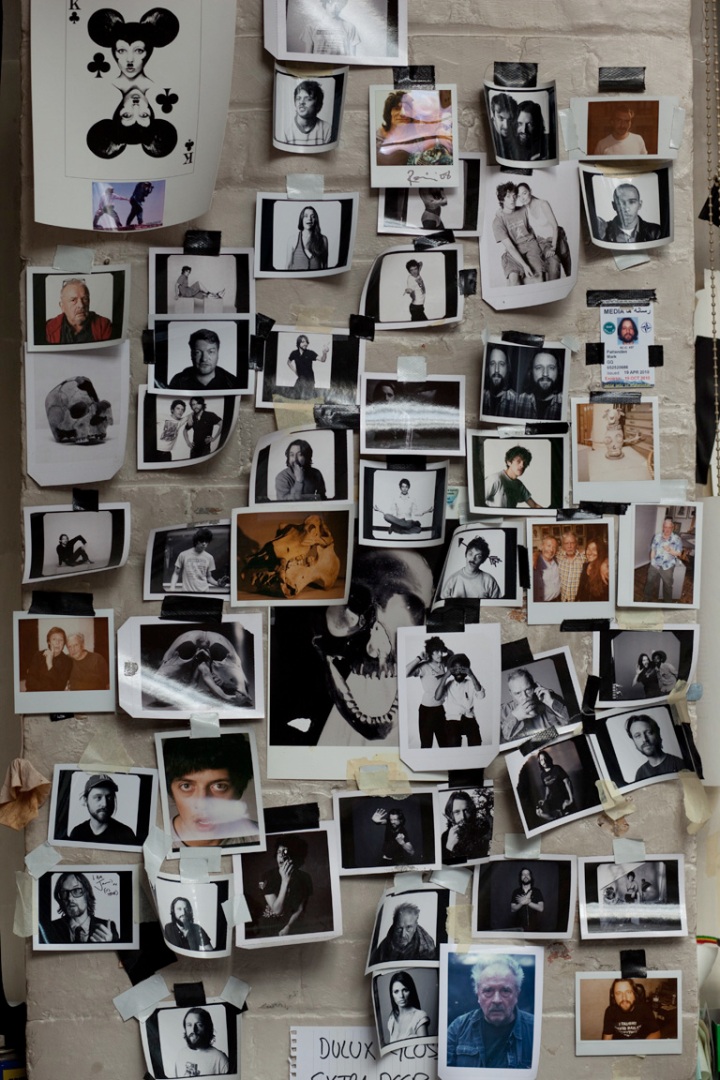

Ascending the stairs into his skylight flooded studio I’m immediately struck by the life that emanates from it. See, the thing is, I don’t know anybody with a studio, a proper studio. These days people have ‘spaces.’ When I need to shoot in a studio I go to one of London’s many rental operations. To a one, they are all sterile, white, cold, soulless blank canvasses that are not intended to inspire anything. I find them torturous places to spend a day in. The idea is that you bring the concept with you and fill the space with it temporarily. The thing is, I make it all up as I go along. Fundamentally, I’m bringing nothing of my own to a vacuum that has nothing to offer. When you leave, a little army of assistants come in like Oompa Loompas and eradicate any memory of your presence there.

Bailey’s gaff, on the other hand, has all the timely grime of his 30 odd year occupancy. Polaroids, one signed by Jarvis Cocker that says “I am Jarvis xx (it’s true)”, bits of weird equipment, postcards, a cage of exotic birds from who knows where, skulls, human skulls, animal skulls, a skull that looks like it was designed by George Lucas, a picture of Mao (is it a Warhol? I don’t know), Bailey with Ronnie Wood, Bailey with Macca, Penelope Tree as a sort of Mickey Mouse King of Clubs, a picture of Bailey’s assistant, Mark, pulling onto the back of Bailey’s trousers as he leans over the edge of a freight container to take a picture in Afghanistan last year.

This place is consumed with life and vitality. I haven’t been in anywhere like this for years. I don’t know anyone that can afford it.

My first sight of Bailey is of him sitting on a stool with a cape around his neck as a young, dark, good looking guy cuts his hair. His voice has that familiar, slightly high pitched old school Cockney lilt to it. He sounds exactly like he did in the Olympus ads he used to appear in on the telly when I was a kid.

“Hello, are you Chris?”

Yes, I say, I am indeed.

“Siddown, siddown, has anyone offered you a drink? Tea? Coffee? This is Kashmir, he’s cutting my hair. What’s that book you’ve got? Is it any good?”

I’m made to feel welcome as Bailey includes me in the ongoing studio conversation with Mark and his P.A., Danielle. It goes on like this for a while. People come and go. His wife Catherine comes in for a while and we all have lunch. Their daughter, Paloma, is floating around the place, doing various bits and pieces. It’s people sitting around talking about stuff. Bob Dylan is on the stereo. Bailey loves Dylan.

He says something about the Kray twins (“Ron and Reg”) and their mother, Violet. I mention that my granddad was from Vallance Road, the same street as the Krays, and that his parents were killed by the last V2 that hit London in March 1945.

“A V2 hit my local cinema when I was a kid. I remember being very upset. I thought Hitler had killed Mickey Mouse.”

Kashmir finishes the haircut, packs his scissors away, is the recipient of a warm farewell from all and leaves. I make a comment to Bailey about what a great name ‘Kashmir’ is for a hairdresser.

“Oh that’s not his real name, that’s just what I call him.”

“What’s his real name then?”

“Oh fuck it, I dunno, Gianni or something. I just call him Kashmir because he looks like a Kashmiri carpet salesman.”

The conversation goes back to my great grandparents and Bailey asks me if they were Jewish and I say that they were.

“So you’re Jewish?”

“No. After the war my granddad anglicized his name and my mum was brought up Christian. We are the black sheep of the family on my mum’s side.”

“You married?”

“Yeah.”

“Your wife Jewish?”

No. English. Posh English.”

“Hmmmm. Shiksa.” (A Shiksa is an attractive gentile girl who might be considered a temptation to Jewish men or boys.)

“Christ! I’m not even Jewish. How can I be married to a shiksa?”

“I once thought I might be partly Jewish. Turned out I’m not.”

He asks me how I got into photography.

“When I was a kid, in the school library I found a copy of ‘David Bailey’s Box of Pinups’.

“Really? Did you nick it?”

“No!”

“You should’ve done. That’s worth about twenty grand now, a complete set.”

I realise I’ve made a mistake. It wasn’t ‘Box of Pinups’, it was ‘Black & White Memories’.

“Oh. Nah, that’s not worth anything. Terrible printing.”

I go on to explain that photography for me was not the end in itself. It’s always been the conduit that has allowed me to meet and talk to interesting people.”

“Yeah? Well you’re in the wrong job then mate. You should’ve been a fucking hotel receptionist.”

A bit later on:

“I like you Chris but I think you’re a bit too fucking serious.”

“It’s hard not to be when I’ve been assigned the straight man’s role in this relationship.”

The time passes and the ‘quick chat’ has turned into 3 hours. I’m getting anxious about the fact that I’ve got to go and pick up my daughter from school.

“Bailey, this has been great. It’s been such a treat to come here and meet you. Thanks for having me but I’ve really got to go.”

“Go? You haven’t seen my darkroom yet.”

Now is my chance to turn the tables.

“Oh alright then. Come on. Quickly. Five minutes and then I’m going.”

For a brief moment I feel like I’m Ernie to his Eric.

We go downstairs and into the darkroom. I haven’t been in one of these for about 5 years and the smell is like crack. Immediately, I want my old one back. We stand around in the red light while he prepares a neg for printing. This is where he seems to really want to be more than anywhere, in the dark, on his own, making prints. Outside, the exotic birds are squawking relentlessly. The red light and the sound of the birds gives me the feeling that we are in a pet shop that doubles as a brothel on quiet days.

I deliberately haven’t pressed him on the Telegraph question, the reason I am here in the first place. I didn’t want it to get in the way of how much I’d enjoyed just hanging out with him and his crew and talking about photography and all sorts of other things. It was, truly for me, a great afternoon, everything that this life can deliver on it’s best days and nothing like what it would have delivered had I become a hotel receptionist. He seems to sense this and says one of the most generous spirited things I’ve ever heard from someone whose opinion, as hard as I might try and pretend doesn’t matter to me, actually matters to me.

“I’ve enjoyed it today, Chris. Before you came I had a look at your work and I like it. I like your portraits. It’s been a pleasure to spend time with you. I don’t know if I want to do this Telegraph thing, not sure that I want to talk about magazines really. My feelings towards them aren’t warm. So if I don’t do this it won’t be because of you. I’d like to stay in touch and maybe we can do something else together. Even if you are a bit serious.”

“Oh fuck off. Stop telling me I’m too serious.”

And with that, we bid goodbye.

The Something Else

Lucy Davies contacts me a couple of weeks afterwards and, sure enough, Bailey does not want to talk to another photographer about magazines and the nature of magazine photography in the presence of The Telegraph. This is fine with me. I sort of had the conversation with him on our meet, so I feel like I got all the juice out of the orange without having to then deal with the pips.

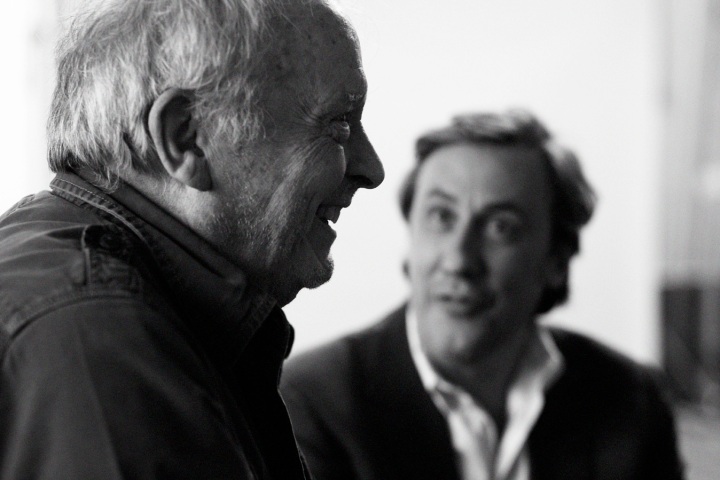

Instead, he is going to talk to Andrew Graham Dixon, The Telegraph’s art critic, about his work in the context of art. He would like me to take his portrait for the piece and it will take place back at his studio.

I put the word out to my assistants and I have a queue of them offering to come and help for free. I take two, Sarah & Andras. We discuss what we are going to do before we arrive. I tell them that, as a matter of pride, I do not want to get one derogatory, sarcastic comment from Bailey about the way we have set ourselves up.

I realize this is futile when Mark, his assistant, wanders over to have a look at our lights.

“Ooh, just you wait till Bailey sees this. He’s gonna rip the piss out of you.”

When he comes in he doesn’t quite do that but he does have a good prod and poke at everything, almost to see if our setup is going to stay up by itself or collapse and fuck up his studio.

I give him a look and start taking pictures.

“If you leave it alone it won’t fall over.”

“What shutter speed you got there?”

“Sixtieth.”

“You sure? Sounds like a thirtieth to me.”

“No, it’s a sixtieth. Stop trying to fuck with me.”

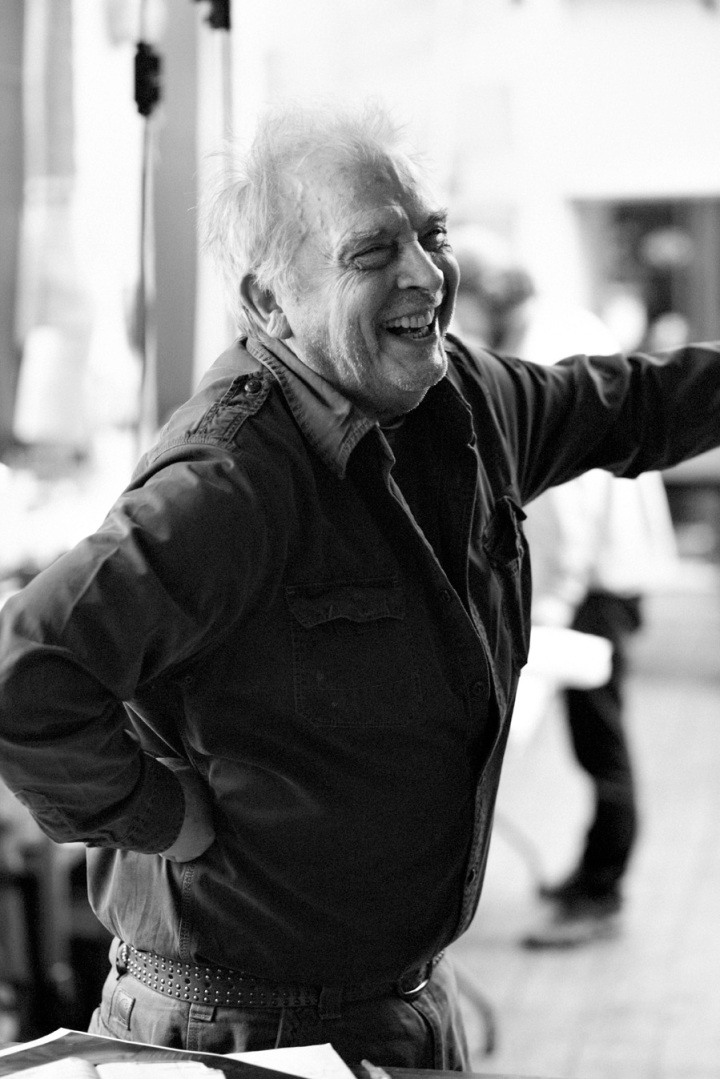

One of the things about Bailey that a lot of people don’t realize is that he laughs. He laughs a lot. He’s got opinions and he expresses them, often to the contrary of other peoples’ opinions but in the process he laughs a lot. He is very funny, which is why he thinks I’m too serious.

We knock the whole thing off in 15-20 minutes. I like doing it quickly. It’s like a plateful of food. Eat it while it’s hot. Too long out of the oven and the glory goes.

“That’s it. I’ve got it.”

“You sure? You didn’t give me any direction.”

“What would have been the point? You wouldn’t have done anything I asked you to anyway. I wanted you as you are. I’ll work around you. I like it like that. I find things I didn’t know I was looking for.”

Still a kid indeed. Still learning. Still fourteen.

Read the discussion that took place between David Bailey & Andrew Graham Dixon in The Daily Telegraph

16 comments